Manning the defenses

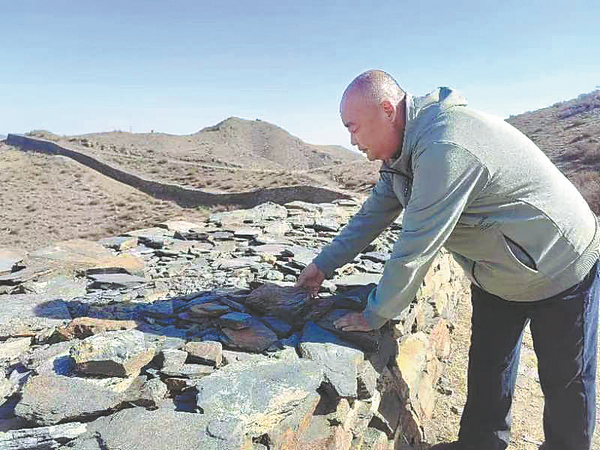

Ancient people used local stones to build the section of the Great Wall in Guyang county, Inner Mongolia autonomous region, more than 2,000 years ago.CHINA DAILY

Over two decades, Luo Heping has made the transition from curious amateur to dedicated protector of the Guyang Great Wall, Fang Aiqing and Yuan Hui report.

Almost 20 years passed like a blink of eye, and in that time Luo Heping has turned from a driver into an encyclopedia of knowledge about a section of the Great Wall in North China's Inner Mongolia autonomous region that dates back to the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC).

Driven by a curiosity and persistence that few would understand at first, his career embodies a spirit that's also embedded in the long-standing historical structure, which has sheltered China and its people for thousands of years.

Luo is now director of the cultural relics preservation center of Guyang county in Baotou. His daily work involves patrolling and protecting local relic sites, as well as carrying out archaeological surveys — he is a gatekeeper of the cultural relics in the area, as he puts it.

The 95.6-kilometer section of the Great Wall that runs through the county has 173 beacon towers and five fortresses, where the troop garrisons and officials lived and stored supplies.

"It's a complete ancient military defense system," Luo says.

This east-west section was originally built in 214 BC, during the reign of Qinshihuang, the first Qin emperor. It was built over the course of five years, and was restored during the reign of Emperor Wudi (156-87 BC) of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) and extended to its current length.

On the Seerteng Mountain, ancient people split stones — a material easy to find in the area, and traces of quarrying have been found — and piled them up to resist the threat of the nomadic Xiongnu tribes from the north.

Luo Heping (right), director of cultural relics preservation center of Guyang, and cultural officials from the city of Baotou, which oversees Guyang county, inspect Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) carvings. CHINA DAILY

The late Luo Zhewen, scholar of ancient architecture, once commented that the Great Wall in Guyang represents the earliest iteration of the Great Wall in China. The section is strategically located and has a unique structure and has been well-preserved ever since.

Dong Yaohui, executive vice-chairman of the China Great Wall Association, says that principles followed in building the Great Wall in later dynasties, like building forts in harsh terrain and using local materials, were already seen in Guyang.

He believed it was the relatively little human activity in the area that accounted for the survival of the Great Wall over the course of two millennia.

When cultural relics preservation experts came to rescue the wall in 2004, Luo was responsible for carrying water and supplies for experts and the construction team who were living near the site.

Tired of waiting long hours doing nothing in his automobile, after completing his work, Luo would watch the experts working on site.

They would introduce to him what they were doing, explaining their process and the terms that he still uses today.

For example, a major part of the restoration was to sort out the wall's foundations, collect collapsed stones, and put them back on the wall, making them staggered and lap jointed — an enduring technique used by the Great Wall builders to make a structure more solid and that is still in use today.

Luo, who has an encyclopedic knowledge of the Great Wall in Guyang, patrols the site. CHINA DAILY

If a stone falls and creates a hollow area, either due to land vibration or water loss and soil erosion, the wall should be mended as soon as possible. Otherwise, the damage may get worse, Luo says.

Some 1.2-km of the Kangtugou section of the wall was restored in 2004. The well-preserved section, located to the north of Guyang's county seat, is 5 meters deep on the outside, 2 meters deep on the inside, 2.8 meters wide at the top and 3.1 meters wide at the bottom, and runs for a length of 3 km.

"I came to work there by chance. I really admired the experts, thinking 'how come they knew so many things?' They told me a lot that I found really interesting," Luo says.

After a while, when he was more familiar with their work, he decided to give it a shot himself. The experts taught him how to photograph the relics — when to use a full view and when to use a close-up, for example — as well as to draw.

In 2006 and 2007, Luo followed the experts and trekked the length of the Qin Dynasty Great Wall in the county to survey the whole structure.

The team accurately ascertained the length of the Great Wall in Guyang and Luo also learned to map the site with GPS technology.

As a low-paid temporary worker, his colleagues wondered why he would bother to climb the mountains, exposing himself to the blazing sun for hours, and getting dirt all over his trousers, which sometimes wore out, simply to do the extra work.

"But after twice walking along the Great Wall step-by-step, I dare say I was one of those who knew it the best in our county," he says, adding that people would naturally turn to him when facing problems with the wall.

"My colleagues recognized my abilities, and I felt proud of myself. That feeling supported me over the long period serving as a temporary worker."

In 2007, he participated in further fieldwork at other cultural heritage sites in Guyang, and got to know the layout and condition of the sites by heart. As a result of that expedition, the registered immovable cultural heritage in Guyang grew from around 30 locations to 159.

In charge of the GPS facilities, Luo had to cover every corner of the archaeological sites, which ended up with him remembering every tree and telegraph pole.

"People are passionate when doing what they love," Luo says, adding that he would get excited, even when finding a pottery shard with patterns on it while on patrol.

It was not until 2012, after eight years working as a volunteer Great Wall conservator and temporary worker, that he finally got a bianzhi (official registration), which means his job is secure and comes with social insurance, healthcare and a pension.

To make up for the knowledge gap, he reads a lot about history, geography and meteorology, and combines his reading with what he sees on the spot and learns from the experts.

Nowadays, drones and advanced map software have made patrols easier, improving efficiency and accuracy and lightening the heavy backpacks they used to carry.

Local residents living near the Great Wall are of great help to Luo's work, as surprise findings might occur following a casual chat, either a new discovery or clues about potential thefts.

During a routine patrol in March 2018, several small, regular holes — around 30 centimeters deep and with a diameter of around 20 cm — near the beacon towers along the Great Wall at Yinhao town caught his attention.

When he went back to his village for tomb sweeping during the Qingming Festival holiday in April, he asked the other villagers whether there had been people digging around the relics. The villagers answered that two people had been seen doing so, but they thought they had been Luo's colleagues doing excavation.

Luo immediately went to check the site and spotted the same holes he had seen in Yinhao. He reported the situation to the police and asked Great Wall conservators to step up inspections.

The 95.6-kilometer Great Wall in Guyang is among the most well-preserved sections built during the Qin (221-206 BC) and Han (206 BC-AD 220) dynasties. CHINA DAILY

Soon after, they caught the pair who had been using a metal detector to locate cultural relics underground, unearthing ancient coins, bronze mirror fragments and other items.

According to Luo, they have been teaching about the Great Wall in nearby villages for two decades in an effort to raise awareness of the need to protect its legacy. Academic seminars were also held to help the villagers better understand and preserve the relics.

Therefore, major conservation challenges have turned to protecting the overall natural environment of the area and safeguarding against destruction caused by intense rainfall, flood, water loss and soil erosion.

According to Luo, who drafted the preliminary plan for the county's Great Wall national cultural park, on the basis of preservation, they will build an exhibition hall of around 300 square meters near the Kangtugou section, which is close to the county seat and has convenient transportation links, to display the history and culture of the Great Wall.

They will also develop cultural tourism centered around the Great Wall near the Chunkun Mountain, a dazzling travel spot around 60 km from the county seat.

Dong's association has been providing intellectual support for grassroots cultural relics preservation initiatives, including that of Guyang, to help people better understand national policies and assist in drafting conservation plans and measures.

He particularly stresses that their planning should suit the local situation.

"Both the historical construction and current preservation of the Great Wall reflect the Chinese people's long pursuit of peace. We don't want war, otherwise we wouldn't have to make so much effort," Dong says, adding that preserving the Great Wall is actually passing on this hope.

"Therefore, we should not only protect the wall itself, but also dig deep into its cultural and spiritual values," he adds.

Both Dong and Luo urge more people to learn about the wall and its preservation and development.

Print

Print Mail

Mail